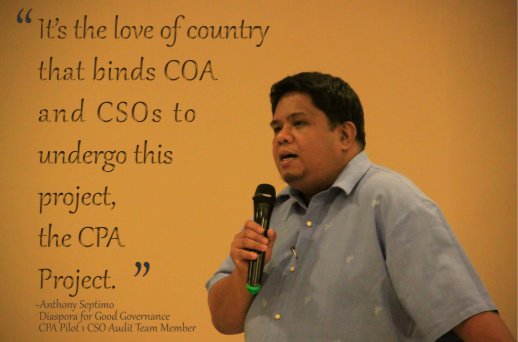

Thirty-four-year-old civil society representative Anthony “Tony” Septimo compares collaboration between the Commission on Audit and citizen organizations to the commitment between married couples.

I have been with many non-government organizations before. We have had some noteworthy engagement with government. But through all these, citizen groups have always taken the role of “watchdog”.

Let’s face it: there has always been mutual distrust between CSOs and government. Government tends to be suspicious of citizen groups, sometimes deriding us as “noisy”. CSOs are perceived as always out to find something wrong with what government does. Civil society, in turn, generally believes that public officials will engage in irregularity especially if they can get away with it.

The citizen Participatory Audit program promised to be different at the onset, and this is why I was eager to join, as project officer and technical staff of the group Diaspora for Good Governance (DFGG). I wanted to know how government audits are conducted exactly. I was also upbeat about the word “participatory” – it promised something different, something inclusive.

I was part of the audit team that looked into the first pilot – the flood control project in the KAMANAVA area. The audit was conducted to find out why there was still flooding in the area despite the existence of a flood-control project. The actual audit process was very enlightening for me. I was able to engage with the stakeholders, especially the community whose lives were directly affected by the project. It was made clear that the objective of the project was not entirely to eliminate the flooding, but to minimize it by x percent. Most of all, I was able to understand more deeply how the Commission on Audit operates.

I learned, for instance, that they really have a mandate to keep quiet about their audit efforts until after the reports have been published. I also understood that there are many steps in conducting an audit precisely because we want to be fair to everybody concerned. The agency gives the auditee some time to explain or react to the findings. That the COA has opened up to citizen participation is by itself a bold action on its part.

I was also educated first hand on the many types of audit – financial, compliance and performance or value-for-money audit. Each type carries different approaches and methodologies.

Now that the first phase of the CPA is drawing to a close, I can say that this project has indeed been collaborative. It was not easy – there were many times that I found myself at odds with my COA counterparts. For instance, it was very easy to mistake their attitude for arrogance. As we completed our partnership however, it became clear to me that this was just their orientation – an institutional contextualization similar to what CSOs have as a default orientation prior to their involvement with the CPA project.

In the end, both sides have similar goals, and that is to ensure that projects are executed well and the people are aware that they have a stake in the projects that directly include them. Just like a partnership inmarriage – you have two people with different backgrounds and values, and sometimes you cannot avoid disagreements. But because of a shared commitment to the union, you persevere to find common ground and try to understand where the other is coming from.

I truly believe that good governance is never the sole responsibility of the government. The best approach to combating corruption and making good governance work is constructive engagement between government and its citizens. I am happy to be part of the CPA where I saw firsthand this dynamic at work.

The CPA has many champions and in fact has been recognized abroad for its unique approach. It was given the Bright Spots Award during the Open Government Summit held in London. I am truly hopeful that beyond being “institutionalized”, citizen participatory audit will be seen in action down to the grassroots level, and will be sustained as a practice from hereon.